Apathy: The Overlooked Symptom [INFOGRAPHIC]

Submitted by Kelly Gilligan and Nettie Harper, Co-Founders

Submitted by Kelly Gilligan and Nettie Harper, Co-Founders

Inspired Memory Care, Inc.

Apathy is one of the most common symptoms among people living with cognitive change.

In fact, research suggests that approximately 80 percent of individuals living in a facility and 36 percent of those living in the community with cognitive change are experiencing apathy. However, apathy is often under-recognized and under-treated, which can lead to a faster disease progression and more problematic symptoms down the line.4

What is Apathy?

Individuals living with cognitive change who are exhibiting apathy may present with the following symptoms: diminished initiation, poor persistence, lack of interest or indifference, loss of social engagement, blunted emotional response or lack of insight.

While apathy can be a sign of depression, it can also occur independently of depression, and each can worsen the other.

If you are unsure about whether a client is experiencing depression or apathy, consult a clinician for an evaluation. The symptoms of clinical depression are often treated with a different combination of medication and therapeutic intervention than the symptoms of apathy are, so it’s important to involve a skilled professional in diagnosis.2

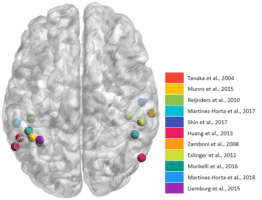

Begins in the Brain

Apathy can have its origins in an individual’s brain, or it can begin as a behavioral response to the psychological and social environments in which a person lives.

When apathy occurs due to brain change, it often starts in the pre-frontal cortex, which affects initiation, motivation and planning. Apathy can also occur due to a phenomenon known as “learned helplessness.”

When challenge is significantly eliminated from an individual’s life, or when the individual is met with negative messaging and feedback over long periods of time, he or she will automatically

begin to defer to a care-partner in lieu of making choices or carrying out tasks independently. This may unintentionally reinforce the behavior.2

Does Apathy Really Matter?

As apathy does not result in an immediate safety risk, it is often overlooked as a behavior — particularly in long-term care settings. However, it can have significant consequences for both the person living with dementia and family.

First, the saying is true: “If you don’t use it you lose it!” Apathy can keep individuals living with dementia from being motivated to participate in activities of daily living. That lack of stimulation can, in turn, bring about a faster cognitive and physical decline.

Apathy Can Be Serious

Research suggests individuals with apathy are approximately three times more likely to have impairment with activities of daily living.3

The effects of apathy are also known to take a toll on family care-partners, who may, in the absence of an emotional response from their loved one, feel a sense of frustration in their roles as carers, and then resign themselves to the idea that their contributions do not matter.

Education is key in supporting both partners to stay active and connected over time.3

More specific negative consequences of apathy may include:

- Contractures, deconditioning (often to the point of needing support from two or more people)

- Fear around movement, fear around touch, increased struggle with care processes (for instance, general movement necessary for walking, bathing, dressing, and other activities of daily life)

- “Shadowing” (complete reliance on the care partner to the point that it becomes impossible to step away)

- Keeping individuals living with dementia from being motivated to participate in their daily care and routine. This can bring about a faster cognitive and physical decline for the individual, as well as a diminished sense of meaning and purpose.

Holistic Treatment of Apathy

The treatment of apathy involves a three-pronged approach: changes in care-partner actions, environment, and (possibly) medications.

The treatment of apathy involves a three-pronged approach: changes in care-partner actions, environment, and (possibly) medications.

Make One Change at a Time

When creating solutions, it is important to make one change at a time and give the individual sufficient time to learn and respond to the change. 3

Start Small

For instance, start with listening to music together rather than expecting a dance immediately.3

Use Positive Language

Instead of “no, don’t” or “let me do that,” as long as there is no safety issue, try saying “yes!” – even if the task is done imperfectly.5

Enlist Help of Allied Therapies

Often, well-meaning loved ones take over processes or decisions in the name of dignity or safety. However, this accidental “taking over” can inadvertently compromise an individual’s sense of self-efficacy and self-determination, resulting in a slippery slope of withdrawal and disengagement.

Often, well-meaning loved ones take over processes or decisions in the name of dignity or safety. However, this accidental “taking over” can inadvertently compromise an individual’s sense of self-efficacy and self-determination, resulting in a slippery slope of withdrawal and disengagement.

Enlisting the help of an allied therapist (occupational, physical, recreational, creative arts or speech therapy) may help with learning new or adapted strategies for tasks so that your client or loved one can remain successfully involved.5

Create an Environment With Cues

In general, individuals living with cognitive change benefit from having one point of focus that matches the person’s skill and interest.

In general, individuals living with cognitive change benefit from having one point of focus that matches the person’s skill and interest.

For instance, long movies or programs with plots that are difficult to follow may be less engaging than musicals, short clips, and other visually engaging images that can be responded to “in the moment.” Cluttered environments may create confusion about what the task is.

So decluttering and creating a supportive area where a loved one or client can focus on one task at a time is very helpful.1

Use Rewards

Some individuals may benefit from a “reward system” for motivation, if they are no longer able to associate abstract benefits with the tasks they are being asked to complete. Think about what the individual truly enjoys, and leverage that.

For instance, some care-partners have utilized scratch-offs, chocolates, and other personally-tailored favorite things. These systems of external motivation should never involve punishment or control, but rather friendly bargaining or “cheering on.”1

Consult a Clinician

Ruling out depression is an important step to determining the course of treatment. Be sure to share signs and symptoms like changes in appetite, expressions of hopelessness or worthlessness, irritability, changes in sleep, or crying if occurring. A clinician may discuss medication options as well.2

A person living with learned helplessness did not develop his or her change in behavior overnight. It is going to take time to “unlearn” the learned helplessness! It’s important to present small adjustments and honor decisions consistently with patience for the individual living with cognitive change and self!

7 Tips to Treat Apathy [Infographic]

Kelly Gilligan and Nettie Harper

Kelly Gilligan and Nettie Harper

Co-founders

Inspired Memory Care, Inc.

Visit Inspired Memory Care on Dementia Map or on their website.

Read more great articles like this one on the Dementia Map Blog!

References

1. Calkins, M P. (2018). From research to application: Supportive and therapeutic environments for people living with dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(Suppl. 1), S114–S128. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx146

2. Fahed, M, Steffens,D. (2021) Apathy: Neurobiology, Assessment and Treatment, Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 10.9758/cpn.2021.19.2.181, 19, 2, (181), (2021).

3. Kolanowski, A, Boltz, M, Galik, E, Gitlin, L N, Kales, H C, Resnick, B, Van Haitsma, K S, Knehans, A, Sutterlin, J E, Sefcik, J S, Liu, W, Petrovsky, D V, Massimo, L, Gilmore Bykovskyi, A, MacAndrew, M, Brewster, G, Nalls, V, Jao, Y L, Duffort, N, … Scerpella, D. (2017). Determinants of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A scoping review of the evidence. Nursing Outlook, 65(5), 515–529. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2017.06.006

4. Manera V, Fabre R, Stella F, et al. A survey on the prevalence of apathy in elderly people referred to specialized memory centers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5125

5. Theleritis, C, Siarkos, K, Politis, A, Katirtzoglou, E, Politis, A. (2018). A systematic review of non-pharmacological treatments for apathy in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 33(2). Doi – https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4783