It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way

It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way

It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way

Submitted by Cyndy Hunt Luzinski, MS, RN

Founder and Executive Director

Dementia Together

SPOILER ALERT: MOVIE DETAILS DISCUSSED!

After Anthony Hopkins won the 2021 Oscar for best actor in “The Father,” our Dementia Together team figured we’d better view the film.

It was as promised: Creatively compelling and hopelessly heart-breaking—everything the cultural tragedy narrative around dementia would have us believe is inevitable and true.

“The Father” shows a former engineer, Anthony (Anthony Hopkins) developing signs of dementia and his daughter, Anne, worrying about how she will care for him as his symptoms progress. When Anne announces she’s leaving to live in Paris, Anthony worries about what will happen to him.

Sometimes Anthony seems perfectly fine, and other times he doesn’t know who Anne is or even ultimately who or where he is. He feels that “this nonsense is driving me crazy.”

As we watched “The Father” and wondered, “Wait, what? Did I miss something?” We experienced the greatest brilliance of the film in showing us as viewers what it might feel like to be confused about recent facts without having a companion alongside us, in what the SPECAL® (pronounced “speckle”) Method calls a “we-relationship.”

Many of us easily take for granted how we automatically reference recent facts in order to manage without anxiety throughout the day. In watching “The Father,” I experienced what I get to teach when I share the SPECAL® Method based on the SPECAL Photograph Album analogy.

The saddest part of the film was that no one even knew the hopelessness they felt was unnecessary.

The SPECAL Photograph Album Analogy

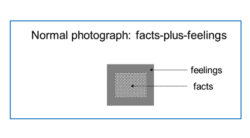

The analogy very simply explains our memory system as a photograph album with each of our individual memories stored as photographs in our album. Each photograph contains the facts and associated feelings of what has just occurred.

The analogy very simply explains our memory system as a photograph album with each of our individual memories stored as photographs in our album. Each photograph contains the facts and associated feelings of what has just occurred.

Photographs are arriving automatically and unconsciously all the time in our albums, providing us with information about the facts of what we have just been doing and how we have felt about it.

With dementia, the experiences continue to store as photographs, but not necessarily with the facts of what has just occurred.

With dementia, the experiences continue to store as photographs, but not necessarily with the facts of what has just occurred.

Instead, the dementia-related photographs store as fact-free, feelings-only photographs which we call “blanks”—meaning blank in terms of facts.

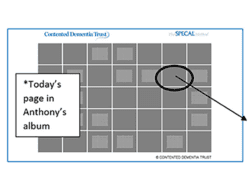

“Today’s page,” like other pages in Anne’s photograph album shows facts and feelings storing coherently. Compare that to “Today’s page” and other current pages in Anthony’s album where photographs are storing, randomly and intermittently, as feelings-only blanks.

Just as we witnessed in the movie, the blanks are stored with increasing frequency, until today’s page is storing only rare normal photographs with the facts and feelings amidst a sea of blanks in which the feelings of an experience take up all the space where the facts would have normally been stored.

When family care partners and professional care providers understand the photograph album analogy, they know WHY their expectations need to be adjusted based on what is storing in the album of a person with dementia. This understanding provides the framework for practicing the SPECAL Method which also shows us WHAT needs to be done and HOW to do it in a way that ensures lifelong well-being for their person living with dementia.

“The Father” gave us as viewers an idea of what it must feel like to have a blanking album. It forced us to ask ourselves, “What happened here?” and “Who’s that?” Like Anthony, we might even have said, “Something funny is going on around here.” We experienced what it is like not to have access to the facts which help us make sense of what is happening.

Anthony didn’t lose his reasoning capabilities or his desire to reason. He’s simply lost recent facts with which to reason.

He very reasonably worked to match his current blank photographs to pre-dementia photographs in his album—photographs with facts and feelings–to help him try to make sense of what was happening in his life. Keeping track of the details in the film was difficult and exhausting, but it made it easier for us to understand why Anthony, too, would be overwhelmed.

Anthony needed a companion who knew to avoid direct questions and contradictions that forced him to consult his album for facts he needed, only to be confronted with blanks rather than the factual information required to answer a question or defend his statement. Confrontation with incontrovertible evidence that you are missing facts about your own life is a potential trauma unlike anything someone without dementia experiences.

Watching the film with the SPECAL Photograph Album in mind, we can almost “see” Anthony anguishing and searching in his album for facts he needed to give him context for what was happening in his life. With or without dementia, we don’t “just know” things. We need to check our albums first for the factual information required to make sense of what is going on in our lives, to be able to ask or answer questions, and to figure out statements which challenge what we thought was right.

The SPECAL Photograph Album analogy allows us to see, almost in slow motion, what happens at lightning speed with normal social interaction. Once care partners understand the photograph album analogy, it becomes clear why common sense doesn’t work, but SPECAL sense does.

SPECAL sense recognizes that the person with dementia may not know the facts of what has just happened in their life. SPECAL sense starts with simple general principles which minimize anxious wondering and lead into fitting other pieces of the puzzle together specific to the person’s life in order to create life-long well-being.

An Atypical Film Analysis

Because the image of Anthony’s album was flashing in my mind while watching “The Father,” I counted 11 times that Anthony was asked, “Do you remember?” or “Don’t you remember?” I noted an additional 71 times when other direct questions were pummeled at Anthony—questions he could not answer because he did not have available facts stored in his album. Logical explanations were given 20 times with the assumption that recent facts were storing for Anthony.

Clearly, they were not.

Therefore, logic and common sense were not helpful. With my pen in hand, I also noted Anthony was contradicted 17 times, forcing him to consult his “album” each time to try to figure out why, coming up with no factual explanation but only a feeling of frustration. This, in turn, led to more blanks filled with anxious feelings entering and storing in his album until, to the surprise of his unknowing companions, Anthony expressed an outburst of anger.

My rough tally of reasons for Anthony’s misery and his responses to unmet needs may not be an exact count but I couldn’t bring myself to watch the agonizing movie again to confirm the accuracy of the numbers.

Starting with the assumption that Anthony, his daughter, Anne, and others in the story were doing the very best they could, the saddest part of the film for me was that no one even knew that the hopelessness they felt was unnecessary. Just because someone loses the ability to store recent facts doesn’t mean they lose the ability to experience, enjoy, and even savor moments.

Changes in the mind for anyone with dementia simply mean we, the people without blanking album pages, need to shift the way we communicate so that we can connect heart to heart, soul to soul, in meaningful positive ways.

Even though, shockingly, no one from Hollywood has requested this, I have re-written the film in my own mind with Anne learning the simple SPECAL approach. She found people to walk alongside her who learned with her how to do dementia care differently—with creativity, kindness, and counter-intuitive strategies.

Anthony had several secure companions (one at a time) who knew how to help him avoid anxious wondering. They still experienced life absurdities. Their lives still weren’t perfect, because life without dementia was never perfect either.

Their lives were, however, good. They are filled with experiences of purpose, laughter, beauty, joy, and hope–not hope in a future cure, but tangible hope in the current care that provides a sense of well-being.

In my version of the film, Anthony’s companions know better so they do better. Therefore, the ending of the story has changed. Anthony is no longer so traumatized and afraid that all he can do is cry out for the security of his mommy. Instead, throughout the story, Anne and the care team are listening to Anthony’s questions and phrases.

We as viewers are able to spot how important both daughters, Anne and Lucy, are to him even though Anthony wonders why Lucy doesn’t come around much anymore. We are able to spot the pride he held in Lucy’s talent as a painter. If Anthony was matching his current feelings to the time when Lucy died, we’d spot what led up to that level of anxiety for him.

We’d also spot how important his watch (keeping track of time) is to him as a security object. We even spot that Anthony surely doesn’t like Paris because “they don’t even speak English there.” All of this information is like gold in telling the family and in revealing to us what is important to Anthony at any given moment.

“Contented Dementia” Isn’t Fiction

When “Contented Dementia” is realized through the use of the SPECAL Method, “The Father” could end with Anthony smiling and engaging in joyful conversation with his companion as they are admiring Lucy’s beautiful painting or the intricacies of his watch, chatting about the ridiculousness of anyone wanting to go to Paris because “they don’t even speak English there.”

That ending isn’t just a fantasy movie ending. It would be entirely possible as long as the people around Anthony learned how to create a “we-relationship” with him, enabling him to make sense of his world without having to look for recent facts that aren’t stored; providing kind companionship which builds his sense of security and confidence; projecting a positive mood to him through eye-contact and a smile; and enjoying moments of beauty, joy, and love with him without requiring him to consult his album in attempts to answer questions or contemplate contradictions that he has no way of figuring out.

When we listen to the experts living with dementia, we make “living well” with dementia the expectation and not the exception.

Like any of our expert friends, Anthony leads the way and his care companions hold the key. Together, we can all retire the tragedy narrative and re-write better stories.

Images used with full permission from The Contented Dementia Trust, Burford England.

Cyndy Hunt Luzinski, MS, RN

Cyndy Hunt Luzinski, MS, RN

Founder and Executive Director

Dementia Together

Visit Dementia Together on Dementia Map!